The Work of Art is a Scream of Freedom – Artree Nepal Open Studio-2017, Collateral with Kathmandu Triennale

The different historical periods in Nepal have introduced different rulers who established and adopted various laws and systems that primarily favored themselves. Consequently, there have always been social, political and cultural discriminations; as well as exclusion, injustice, and instability. There have been conflicts and struggle for demanding reforms against such injustice that prevails in the country.

In the year 1996, Maoist rebels accused the ruling monarch and the mainstream political parties and labeled government forces as “feudal forces”. As a result, that led to a decade long civil war which claimed the lives of 17,000 people, a displacement of an estimated 100,000 more, and brought about the end of a 240-year old monarchy.

The conflict brought out the voices of marginalized people to the national agenda – particularly of groups like Madhesi, Dalits (the ‘untouchables’), women, the landless and indigenous people — and widened the political space to articulate their grievances. The result was a series of protests and movements across the country by the Madhesi (people from the Tarai lowland) and indigenous people. Yet, very little progress has been made, challenges remain and the country continues to be politically unstable.

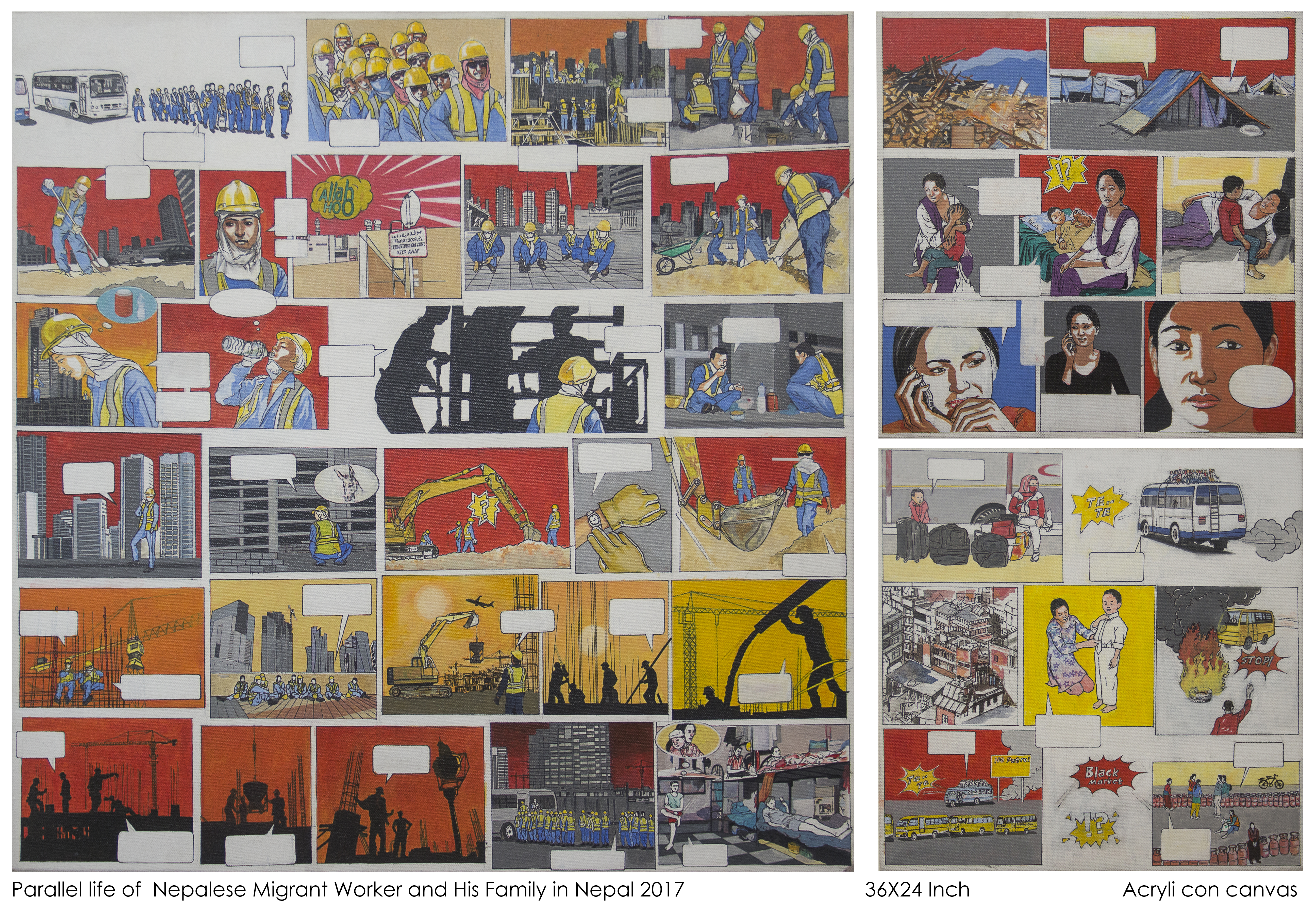

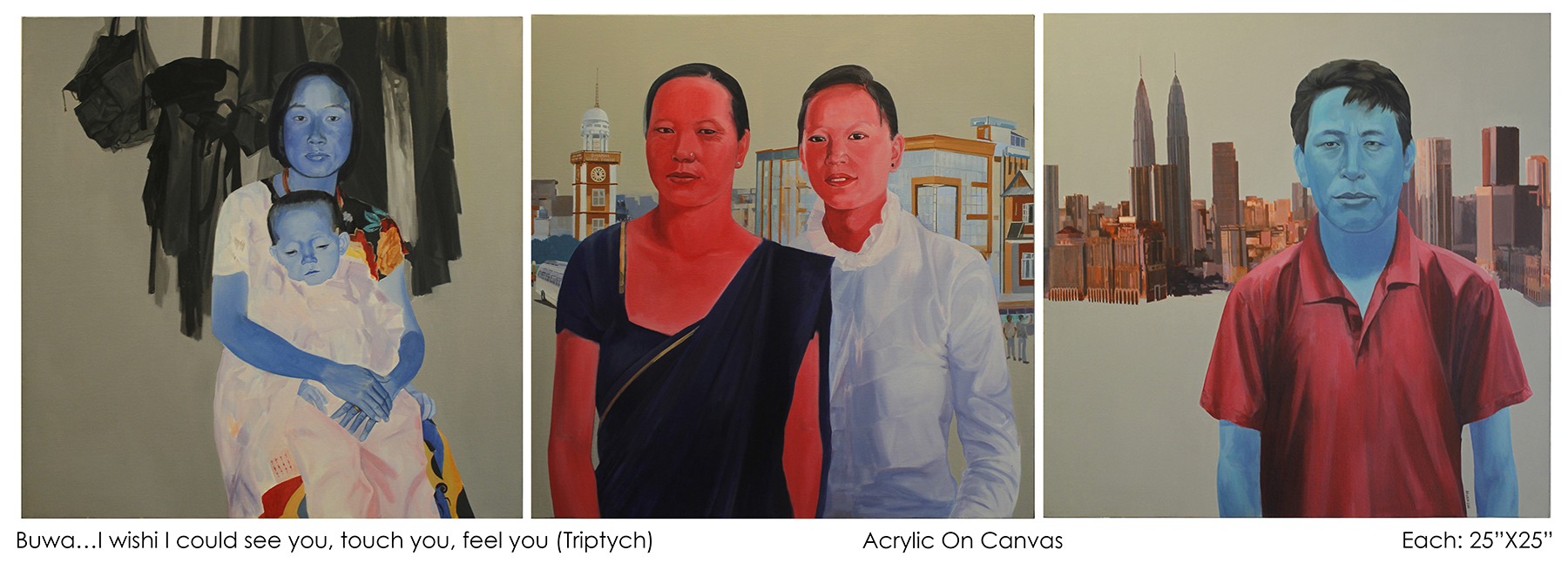

During the Maoist civil war, internal and international mass migration increased exponentially. After the civil war, continuous political conflicts and an unstable government have ignited violence, chaos and uncertainty in the country. This has caused an unexpected rise in mass migration, especially over the past decade, and especially to the Middle East where Nepalese continue to go in unprecedented numbers in search of employment and a better livelihood.

As more and more Nepali citizens aspire for foreign jobs and depart their homeland, profound changes have occurred in the socio-economic fabric of the country. Although the labour migration phenomenon has emerged as an alternative livelihood opportunity for many Nepali households, it imposes new challenges for the government and policy-makers in implementing and managing safe migratory flows between the countries of origin and destination.

Hitman Gurung’s work, ‘Labour’s Helmet’, from the series “I Have to Feed Myself, My Family and My Country…” deals with Nepali migrant labours who leave their families and country to join transitory work forces in foreign countries. These larger economic forces have long-lasting and often unalterable impacts on the global economy as well as on individuals, communities and societies. Emerging from his concern about this phenomenon, Gurung’s work addresses these various impacts.

Mekh Limbu’s work entitled ‘Silent Portraits in Qatar and Kathmandu’ has captured the silent and still portraits of migrant workers in Qatar. He has juxtaposed these portraits with a time lapse video of Kathmandu, indicating his own shifts around different places in the city. With the help of remittance cash sent by migrant workers, families move to bigger and more developed towns and cities within the country in search of a better and brighter life. Limbu’s work demonstrates how international migration has triggered rapid internal migration in Nepal in the past two decades.

Bikash Shrestha’s work, ‘The Family Album’, is a commentary on the mobility of family members and its impact within individual families. People leave their homes and relocate in different places in search of a better life. As a result, small villages and communities get deserted. Members from a single family are scattered across the globe. Only the toothless population (the very old and the very young) are left behind as a representation of an entire family.

Subas Tamang’s work, “I Want To Die In My Own House”, is an autobiographical commentary that also represents the dreams of thousands of dislocated family members in Nepal who move from small villages to bigger towns and cities. When people move, they usually rent a room, compromise with the situation, and struggle for survival. A permanent address is an important marker of a person’s identity in our culture that symbolizes wealth and prosperity. This wish may come true for some but the uncertainty remains. The continuous challenges of securing their daily breads and a decent livelihood – as well as nursing a hope to have a permanent roof above their heads – often traps families in an unending and vicious cycle of struggle.

Sheelasha’s art work ‘Agony of The New Bed’ brings out the ignored reality of gender discrimination. In traditional arranged marriages of Nepal, ownership of a daughter is transferred from a father to a husband. Thus, a girl’s identity and dignity are dependent on her husband after her marriage. Brides are socially forced to shift their identities and adopt their husbands’, just like they are made to abandon their own surname and house and adopt their husbands’. A new bride’s life revolves around uncertainty as she has to shift to a new family, a new space and a new social circle. Numerous social researches have documented the fact that a high proportion of young married females (as opposed to those unmarried) become victims of domestic and sexual violence. Marital rapes are not uncommon. Unfortunately, social pressures and brides’ immaturity restrict them from speaking up in self-defense, even in extremely harsh conditions. And the tradition has been continuing from generation to generation, with only little changes.

Lavkant has explored issues related to Tharu peoples’ identity in line with larger issues of indigenous equality and social discrimination. His work is an annotation to the state violence perpetrated on the Tharu people in the aftermath of the protests that took place after the promulgation of the constitution of Nepal in 2015, where the Tharus raised their voice against political and economic inequality. The bullets, suppressing various grains and flours, represent this violence against Tharu people’s destructed homes and habitations.

Chasma Magowa is a Selfie or Selfish? Exposing oneself on the media, especially on social media, depends on a user’s or a creator’s choice. But looking at and commenting is the choice of a viewer. Sachin borrowed spectacles and glasses from his relatives and friends and then took selfies at different times, during different events and places in search of a connection. This photography-based works ironically represents the situation of a large population who are influenced and connected by cyber culture.

Scream comes out of agony, grief and struggle that people experience in their lives. We all expect happiness, equality, and prosperity in any situation but the reality for many Nepalese is the harsh, laborious condition of deserts, the extreme mountainous cliffs and difficult inner conflicts and dilemmas with regards to individual desires and boundaries within concrete and abstract walls. In any given situation, people scream for the sake of freedom.

“The Work of Art is Scream of Freedom” title for open-studio is taken from the statement by prominent artist Christo Vladimirov Javacheff.

ArTree Nepal

Artists Collective

Participant Artists

Bikash Shrestha, Hitmaan Gurung, Lavkant Chaudhary, Mekh Limbu, Sheelasha Rajbhandari, Sachin Yogol Shrestha Subas Tamang

Open Studio

Date : 2-15 April 2017

Time : 10 am to 7 pm

venue : ArTree Nepal, Samarpan Margh, Tripureshwoar, Kathandu

Shree Janaki Budha Subba Primary School, Kurule tenupa-6 Sogum, Dhankuta

Shree Janaki Budha Subba Primary School, Kurule tenupa-6 Sogum, Dhankuta

Kurule Tenupa VDC, From MudebashVDC, Dhankuta

Kurule Tenupa VDC, From MudebashVDC, Dhankuta